At Macrina, we are increasingly turning to freshly-milled local flours. Both of our newest loaves, the Skagit Valley Sourdough and our Whole Grain Baguette sold at PCC Natural Markets, are made exclusively with locally grown wheat and freshly-milled flours.

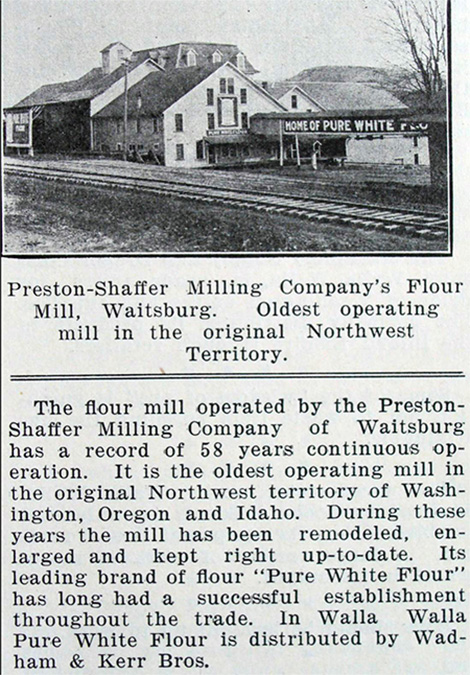

Photo Courtesy of Joe Drazan and the Bygone Walla Walla Project

Twenty miles to the northeast of Walla Walla is the small town of Waitsburg, once a mill town. Now, it’s better known as a side trip for epicures out on a food and wine tour of Walla Walla. A summer drive there takes you through some of the most scenic wheat country: soft undulating Palouse hills covered in golden wheat, glimpses of the distant blue mountains, a gently winding road, and weathered grain silos.

The History of Mills

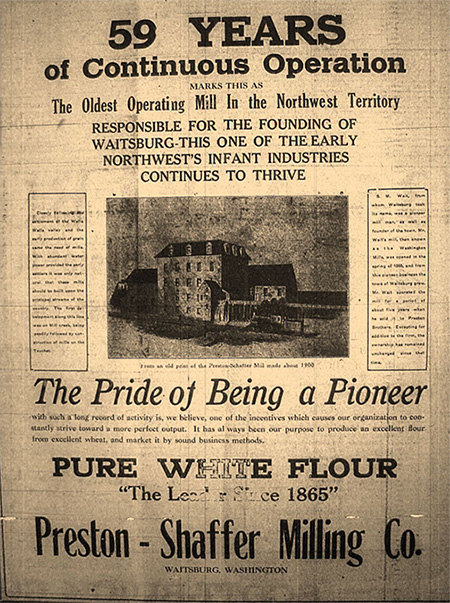

Until 2009, the old mill loomed at the end of Main Street. Then, it burned to the ground in a mysterious fire. The mill was just one of the three early mills still standing in the state when it disappeared. At one time, there were nearly 160 mills in Washington State. The mill that Sylvester M. Wait built in 1865 preceded the town that grew up around it, employing generations of millworkers until it closed in 1957.

Photo Courtesy of Joe Drazan and the Bygone Walla Walla Project

Though not native to the state, wheat thrives in Washington. It was first planted at the Hudson Bay trading post at Fort Vancouver in the 1820s. Early settlers learned that the soil and the climate made for abundant harvests. As the state’s population boomed, new arrivals filled every corner in Washington, and they planted wheat. But what grew well in Skagit Valley was different than what suited the drier climates of Walla Walla County. An incredible diversity of wheat flourished statewide. By the 1880s, transcontinental railway lines pushed through Washington, and mills like the one in Waitsburg could finally get their inexpensive, high-quality wheat to the bigger populations West of the Cascades. Still, local mills in the coastal regions continued to grind local grain, and many small farms across the state grew a variety of grains, some for flour, some for feed.

The local mill was pushed to the point of extinction by turn-of-the-century technological change that ushered in a commodity flour with a very long shelf life. One by one, the local mills folded and wheat production became increasingly centralized. By the time the Waitsburg mill closed, it was one of the few early rural mills still operating.

Photo Courtesy of Joe Drazan and the Bygone Walla Walla Project

Wheat breeders refined wheats for high yields and ease of processing. By 2005, there were only two operating flour mills in Washington State, both producing primarily commercial-grade white flour. The effort to create uniform flours that didn’t spoil created vast quantities of flour, but also took much of the flavor and nutrition from our flour and the products made with it.

Local Wheat Renaissance

Fortunately, we are in the midst of a local wheat renaissance driven by the artisan bread movement and the invaluable research, wheat breeding, and educating done by Dr. Stephen Jones and his team at the Bread Lab located in Skagit Valley. We have mills specializing in grinding whole grain heritage wheats popping up, including Cairnspring Mills, in Skagit Valley, and the Fairhaven Organic Flour Mill, in Burlington. Both produce excellent fresh, stone-ground flour with superior flavor, nutrition and baking properties. At Macrina, we are increasingly turning to freshly-milled local flours. Both of our newest loaves, the Skagit Valley Sourdough and our Whole Grain Baguette sold at PCC Natural Markets, are made exclusively with locally grown and freshly-milled flours.

The Waitsburg Mill may not come back, nor many of the small, forgotten wheat towns. However, the diverse flours they once produced are returning for the same reason early settlers planted wheat everywhere: the taste that freshly milled whole grain flours provide.

Leslie